Marriage pre-civil registration: some thoughts part two.

Continued:

It was a legal entitlement of marriage within the Church of Ireland either to have banns read out in church three weeks in a row, or for a licence to be issued. Many couples opted for marriage banns, whilst some opted for a marriage licence, which was effectively a document authorizing a couple to marry. A license was issued by the Bishop of the Church of Ireland diocese in which a couple lived, and in order to be granted a license, a couple was required to make an allegation of intent to be married and post a bond ensuring that all information given was valid. Marriage bonds and allegations were records created for licensed marriages. Such a bond had to be entered into before a Bishop would grant his licence for a proposed marriage. The parties lodged a sum of money with the diocese to indemnify the church against their being an obstacle to the marriage; in effect, this system allowed the well off to purchase privacy. Most original marriage licences were destroyed in 1922 but some indexes to these have survived (for example the diocese of Down and Connor, 1721-1845 see PRONI: MIC/5B/5 A-F; MIC/5B/6, G-Z].

The banns of marriage are the public announcement in a Christian

church that a marriage is going to take place between two specified persons.

The purpose is to enable anyone to raise any legal impediment to it. Obligatory

notification of the intention to marry was to be given in church on three

consecutive Sundays (but written records of these are relatively rare). Couples were ‘allowed

proclamation’ that having satisfied the minister’s criteria, he allowed the

banns to be read out and posted up. Sufficient time was, therefore, allowed for

the preparation and proclamation of marriage banns on three successive Sundays

prior to the wedding. When anyone applied to have banns published a fee was

lodged. Banns were published and read in two parishes, which added to the cost.

The importance of proclamation may be seen from the fact that the Presbyterian

Synod of Ulster in 1701 unanimously approved that a minister who transgressed

the rule of proclamation ‘three several Sabbaths shall be rebuked and suspended

at the discretion of the Presbytery, whereof he is a member’.

It was a legal entitlement of marriage within the Church of Ireland either to have banns read out in church three weeks in a row, or for a licence to be issued. Many couples opted for marriage banns, whilst some opted for a marriage licence, which was effectively a document authorizing a couple to marry. A license was issued by the Bishop of the Church of Ireland diocese in which a couple lived, and in order to be granted a license, a couple was required to make an allegation of intent to be married and post a bond ensuring that all information given was valid. Marriage bonds and allegations were records created for licensed marriages. Such a bond had to be entered into before a Bishop would grant his licence for a proposed marriage. The parties lodged a sum of money with the diocese to indemnify the church against their being an obstacle to the marriage; in effect, this system allowed the well off to purchase privacy. Most original marriage licences were destroyed in 1922 but some indexes to these have survived (for example the diocese of Down and Connor, 1721-1845 see PRONI: MIC/5B/5 A-F; MIC/5B/6, G-Z].

Irregularity continued to be a problem before

compulsory civil registration and the legitimacy of a marriage contract could

be challenged on a variety of grounds such as the failure to publish banns, not

seeing that banns were published in the other congregation, not being orderly

proclaimed or being only twice proclaimed, being married without consent of

parents, marrying an unknown person, or at the ‘back of the hedge by a spoilt

priest.’. In some cases of irregular marriage, the parties, after censure, were

remarried but this appears to have occurred only in cases where the officiating

person at the offending ceremony was a ‘debarred’ clergyman. However,

irregularity did not always mean that a marriage was invalid, as the presence

of witnesses and consent were at the heart of the marriage contract.

There are serious gaps

in ecclesiastical registration in most parishes. Of course, other sources exist

apart from church registers that might help in this regard, for example, local

and regional newspapers often carried marriage announcements, particularly from

the merchant classes and those of higher social rank. The marriage of ‘Mr Samuel Bryan of

Coleraine, merchant and Miss Kitty Hyland of said town’ was recorded in Finn’s

Leinster Journal of August 1767, which was two years before the earliest

ecclesiastical register was begun in Coleraine (Finn’s Leinster Journal: No. 58 Saturday 8th – Wednesday 12th

August 1767). Other genealogical sources that might contain marriage

details or arrangements include the registry of deeds, indexes to marriage

licence bonds and grants, wills, printed pedigrees, military records, and

ecclesiastical court records. Church registers and comparative sources,

however, are usually only available for limited areas and limited periods but

many early registers do record marriages over a wide geographical area.

With regard to the establishment of the planted settler community in

the seventeenth century and its evolution in the eighteenth century, evidence

suggests that a broader economic and social kinship network was in operation

that went beyond parish, barony and even county. An examination of the early

registers for Templemore, (St Columb’s cathedral), from 1642 and Ballykelly

Presbyterian Church (marriages 1699-1740) confirm that marriages were often

contracted over a wide geographical area. Although some of the cross-currents

that determined such contracts were complex it seems that both mercantile and kinship

bonds were the key factors in operation that affected marriage settlements in

this period. For those interested in local or family history in the early

modern period research methodologies need to take into account that interaction

within the settler population covered quite an extensive geographical area and

nuptial arrangements were often determined by such factors as an earlier or

previous familial connection, merchant networking, sharing a common landlord,

or belonging to the same landed estate.

The clergy of the established Church of Ireland were not required by

canon law to keep parish registers until 1634. Templemore parish is only one of

five extant church registers in the whole of the island, which pre-date 1650

and the registers are a fairly complete set of births, marriages and deaths

dating from 1642. The registers indicate that there was a degree of interaction

between families in the two largest urban centres, Derry and Coleraine. Eleven

marriages were recorded in the Templemore registers in the period 1650-1771

where either bride or groom was a resident of the Coleraine area. Most likely

these marriages occurred as a result of economic interaction between the two

largest towns in the county and the consequential merchant activity and social

networking. Mercantile and social contacts could of course extend to any part

of Ireland or the British Isles, and examples include the recorded marriage

between James Ferguson of Coleraine and Mary Rainey of Dublin in 1747 as noted

in the Betham Abstracts and the marriage of Michael White, Esq, an eminent

surgeon in Dublin to Miss Neill of Woodtown, Coleraine in 1770 (Finn’s Leinster Journal: No 94: 21st

November 1770).

An analysis of Ballykelly Presbyterian marriage register reveal that

the church served the needs of Presbyterians from the contiguous parishes of Faughanvale,

Tamlaght Finlagan (Ballykelly) and Magilligan. The Reverend John Stirling, the

minister from 1699-1752, (son of the Reverend Robert Stirling and Marion

Campbell of Dervock, Antrim) kept a note-book of marriage proclamations,

1699-1740. The register reveals that there were obvious close ties between the

Ballykelly congregation and the other parishes in the Roe valley and across the

Foyle Lough to Donegal, and Inishowen in particular, which was connected by

regular ferry. However, there was also a remarkably strong connection between

the Ballykelly congregation and the parishes/congregations in the Coleraine

district and there is mention in the registers of Aghadowey, Ahoghill, Ballymoney,

Ballyrashane, Ballywillin, Ballyachran, Billy, Boveedy, Dervock, Desteroghill,

Dunboe, Errigal, Finvoy, Kilcronaghan, Killowen, Kilrea, Loughgiel, Macosquin and Rasharkin. Sixty-nine marriages, dated between 1701

and 1740 have been identified that lists a spouse resident within Coleraine and

liberties or just across the Bann into the west of county Antrim. In addition,

marriages were recorded with spouses resident in counties Donegal (Burt, Fanad,

Killea and Raymoghy), and Tyrone (Badoney, Derryvullen, Donagheady and

Donaghmore).

This may indicate that even into the early eighteenth century that

pockets of Protestant settlements were not self-sustaining and therefore, it

was necessary to arrange nuptial contracts beyond parochial boundaries. There

may also have been established connections through trade and merchant activity

as the Roe valley was within easy reach of Coleraine, which was much closer to

Limavady than Derry. The two regions, the Roe and the Bann valleys were amongst

the most Scottish regions of the county and Presbyterianism was the predominant

form of Protestantism in these areas. The establishment of a strong Scottish

colony in north of the county in the early seventeenth century was a result of

a planned settlement under the auspices of Sir Robert McClelland of Bombie,

Kirkcudbrightshire, who became the common landlord of both the Haberdashers’

estate (1616) centred on Artikelly and Ballycastle in Aghanloo parish and the

Clothworkers’ estate (1618) centred on Killowen/Articlave. His vast estate,

which stretched from Coleraine right down into the heart of the Roe valley at

Limavady, became a bridgehead for Scottish entry into the north of the county.

The relative closeness to Scotland may have encouraged further migration.

Families became established in the north of the county encouraging colonial

spread.

Many of McClelland’s relations, extended family, neighbours, and

tenants from his Scottish estates in Kirkudbrightshire moved to his new estate

in north Derry. An examination of the hearth money rolls (1663) for the

parishes that made up McClelland’s estates reveal that there were many families

of the same surname, more than likely related, living on both McClelland’s

Haberdashers’ and Clothworkers’ lands. These strong family bonds and kinship

ties that were established and forged in the early plantation period continued

into the early eighteenth century in the contiguous parishes that made up

McClelland’s vast estate. Deep rooted familial bonds endured well into the

Georgian period and kinship and economic ties were maintained as marriage had

both a social and economic function. Merchant families of course maintained broader social and economic

networks and I have also noted two marriages of Coleraine inhabitants to

spouses from Argyll in Scotland both dated to the earlier part of the

eighteenth century. There is recorded in the Argyll Sheriff Court book a deed

(dated 1720) of a marriage made in 1706 between Isabel, daughter of Duncan

Campbell of Elister to Alexander Stewart, a saddler of Coleraine. Also, recorded

in Christchurch, Limavady, Church of Ireland register in 1730 is the marriage

of Duncan Campbell, Laird of Sunderland on the island of Islay, Scotland to

Esther Law of Coleraine.

The church registers reveal a number of

interesting trends highlighting the seasonal pattern of marriage with fewer

marriages recorded in March during Lent. The 24th of March was the

final day of both the church and calendar year (before the change to the

Gregorian calendar in 1752). Before the onset of civil registration there was no coherent pattern of marriage

registration. Contracting marriage in the Church of Ireland ensured legality but there is a decided scarcity of marriages recorded in many local registers in the period before civil registration. In penal times Catholics appear to have married in houses as there were few churches available and as a result few registers exist before 1800. Presbyterian grievance existed concerning the efficacy of their marriage rites, which occasionally were challenged in the courts. In small enclosed parochial localities marriage regulations would have seem complicated with Civil Law and Canon Law viewed as an impediment thus best ignored. Clandestine marriages were probably common. Some clergymen were willing for a fee to marry couples in secret in irregular marriages. This might have been necessary for a number of reasons, for example, objections of parents, problems with religious affiliation or lack of finance. These marriages may not have been recorded but were still valid in civil law.

It seems like whether a couple paid a bond or used banns might be another way get a sense of the life our families lived back in the day. Does your research provide an indication of the level of affluence that might be assumed if a couple paid a bond instead of using banns? Would the cost be shared by the bride and groom or paid by just one of them? In these relatively small populations would people have generally married people of similar affluence or was there substantial socialization/marriage across socioeconomic lines? Thanks very much for sharing this information. Kerry Dunn

ReplyDeleteThanks Kerry,

DeleteThe survival of marriage records in Ireland is piecemeal pre-civil registration and so it is difficult to draw conclusions as a result.

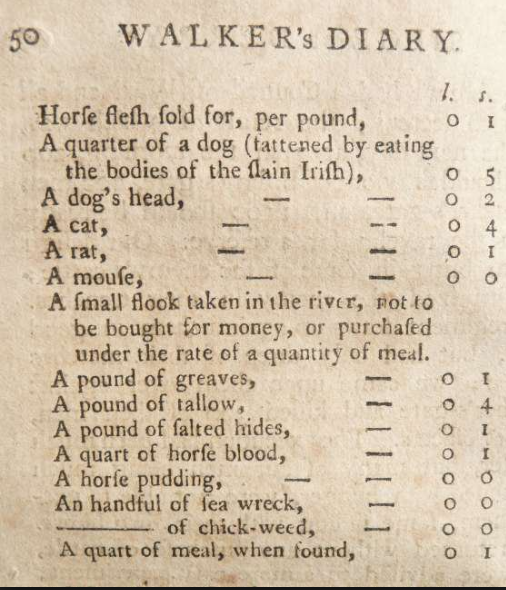

Banns were the most common means of proclaiming marriages in your local parish for three consecutive Sundays. As a result everyone knew your business. Those who were better off or had pretensions of gentility could obtain a licence at the registry of the appropriate jurisdiction where they made an allegation that there was no impediment to marriage (sometimes a money bond was provided as security). Licence was more expensive than banns.

Hence, couple beggar ministers were popular as they provided the cheapest service. I think a lot of folk resorted to this means but very few records survive (if the ministers kept any registers at all!).

The registers for Dr Schulze in Dublin, who was variously known as the ‘German’ or ‘Dutch’ minister, and was minister of the Lutheran Church in Poolbeg Street, Dublin. Schulze have survived. They reveal that he married over 6,000 couples between 1806 and 1837. The surviving registers show him performing at least one marriage a day, and on some days as many as sixteen. Schulze obviously fits into the category as a couple beggar minister.