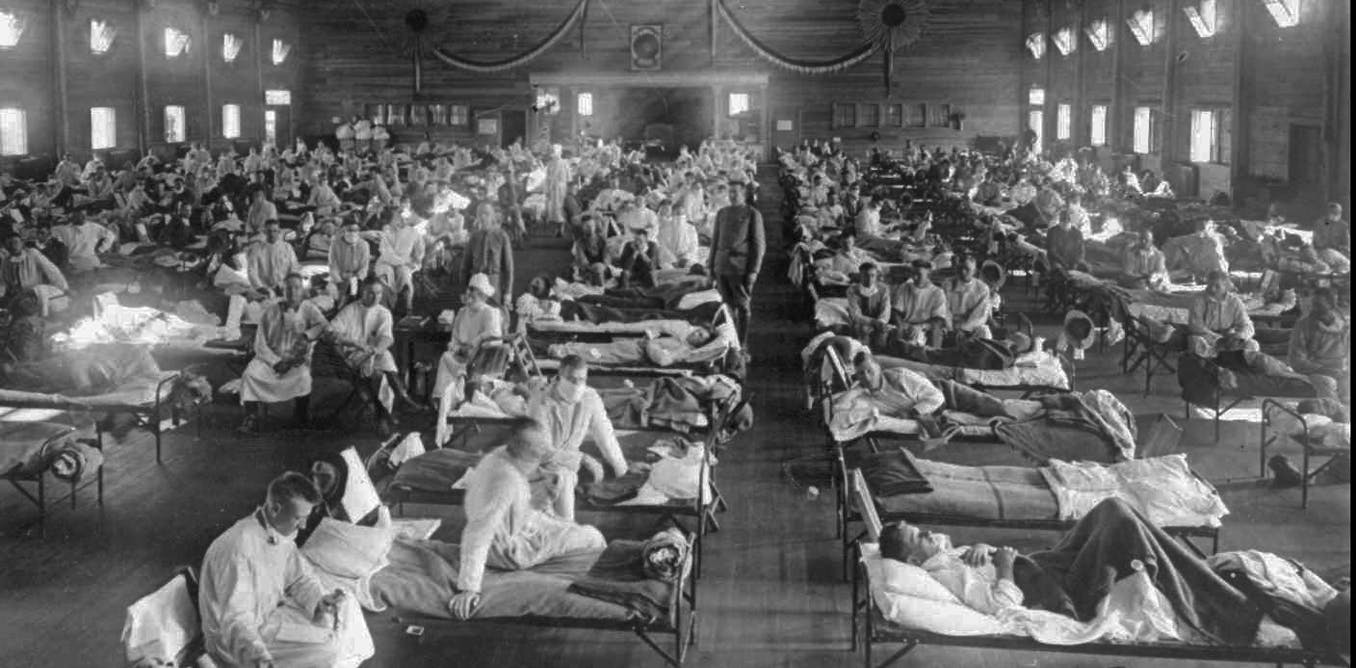

Spanish Flu outbreak 1918

SPANISH FLU 1918-1919 - the greatest pandemic in History:

Estimated death total worldwide = 50 to 150 million

The last major global pandemic occurred 100

years ago in the summer of 1918. Spanish flu was first reported in the early

summer of 1918 by newspapers in Spain,

unaffected by wartime censorship. By then, the US, French, British and German

armies were already troubled by it.

In Ireland 20,057 people were reported as

having died of influenza in 1918 and 1919 (the average annual rate for the

preceding years of the war had stood at 1,179). In addition, an increase in

deaths caused by related illnesses, most notably pneumonia (from which over

3,300 died above what would usually have been expected), can be attributed to

the epidemic.Sir William Thompson, the registrar-general, admitted that the

official influenza mortality rate was a conservative estimate, and there are

reasonable grounds to assume that additional influenza deaths in Ireland were

uncertified, attributed to other illnesses, for example pneumonia and often

simply not recorded at all.

There were three outbreaks, and perhaps a

fourth. The first wave peaked was in early summer 1918, and peak of the second

wave in late October 1918 and the third in the spring of 1919. But even though there were peaks, it was

really continuous for about 15 months from June 1918.

The first wave, which hit Ireland in the

early summer of 1918, was the least destructive, although severe enough for

schools and businesses to close. After the first (and mildest) wave in the

early summer, people questioned what all the panic had been about. The earliest

verifiable record of its arrival in Ireland can be found in US naval archives,

which document an outbreak on the USS Dixie, docking outside Queenstown (Cobh),

in May 1918. On 12 June the Belfast News-Letter reported that Belfast had been

struck by a mystery illness resembling influenza. By the end of June there were

reports that it had reached Ballinasloe, Tipperary, Dublin, Derry and Cork.

Nevertheless, by mid-July the first wave had abated.

The second wave, from mid-October to

December, was the most virulent of the three; and, as in the first wave,

Leinster and Ulster were worst affected. The almost equally severe third wave,

which lasted from mid-February to mid-April 1919, affected Dublin again, as

well as the western part of the island (in particular Mayo and Donegal). As

influenza moved through towns and communities, schools, libraries and other

public buildings were closed, and court sittings were postponed. Businesses

closed sporadically on account of staff illnesses. Medical officers of health,

mainstays of the Poor Law medical system, worked around the clock to treat

their patients, paying 100,000 more home visits during the epidemic than in the

previous year. Hospitals and workhouse infirmaries struggled to cope with the

numbers of patients, pharmacists worked long hours to dispense medicines, and

mortuaries, undertakers and cemeteries had to queue the dead for burial.

Some areas suffered severely during all three

waves, notably Dublin, where troops returning from the war may have been a

major factor. Dublin county and borough had in 1918 a death rate of 3.7 per

thousand living (1,767 flu deaths) and of 2.3 per thousand living (1,099

deaths) in 1919. At 3.85 per thousand, Belfast had one of the highest death

rates in 1918, but in 1919 it had one of the lowest—0.79 per thousand. Some

counties almost escaped the epidemic. Clare, for example, had the lowest death

rate from influenza of any county in 1918, at 0.46 per thousand. Kildare had

the highest influenza death rate in 1918—3.95 per thousand (263 deaths). Water

and power shortages in Naas during the height of the second wave contributed to

a particularly severe local outbreak in the county.

A global peculiarity of the 1918–19 pandemic

was its targeting of normally healthy young adults. In 1918, 22.7% of all

deaths from influenza in Ireland were of people aged between 25 and 35; in 1919

the figure for this age group was 18.95%. The registrar-general estimated that

there were more male than female deaths from influenza in Ireland, which

contrasted with the rest of the United Kingdom, where slightly more female than

male deaths were recorded. Ulster followed the British pattern, as the female

influenza mortality was slightly higher than the male, especially in the more

industrial areas of the province. There were high proportions of women

textile-workers in Belfast, Derry, Lurgan and Lisburn, and the overcrowded,

hot, damp conditions of linen workshops encouraged the spread of influenza. In

Belfast females between 25 and 35 had a higher influenza mortality rate than

any other age or gender group in the city.

Individuals employed in occupations involving

close contact with the general public were more likely to contract influenza.

Doctors and nurses were particularly exposed. The high number of Dublin

teachers suffering from influenza in October 1918 led to the closure of schools

in the city. Absence owing to influenza depleted police forces throughout

Ireland. Public transport employees were also vulnerable, and in Belfast 100

tramway employees were absent with influenza during July 1918, and 120 in

November. Priests and clergymen were also in the front line, and a lot of them

died. Staff illness forced the closure of shops, with many shopkeepers and

assistants dying.

In Ireland, there are 20,000 deaths directly

attributed to the influenza, also an A H1N1 variant. Another 3,000 people died

from pneumonia following influenza. These figures would suggest in excess of

800,000 cases here, given a death rate of 2.5 per cent. During one week at the end of October,

hundreds were reported ill in Naas, Dundalk, New Ross, Wexford, Gorey,

Kilkenny, Bray, and thousands in Dublin.

Applying to official mortality figures an

estimate that only 2.5% of those who caught influenza actually died suggests

that there were over 800,000 influenza cases in Ireland, 20% of the population.

Between June 1918 and April 1919 the epidemic, which further taxed a health

service already struggling with war-related shortages of medical personnel and

hospital beds, temporarily incapacitated urban and rural communities across the

island.

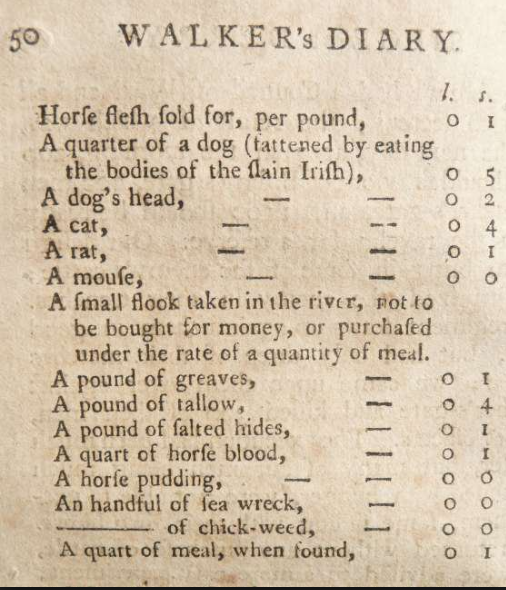

Summing up the local effects of the epidemic

in its immediate aftermath, Sir William Thompson noted that ‘Since the period

of the Great Famine with its awful attendant horrors of fever and cholera, no

disease of an epidemic nature created so much havoc in any one year in Ireland

as influenza in 1918’.

But, surprisingly, it has not featured in

Irish historiography. The ground-breaking documentary Aicíd, screened on TG4 in

November 2008, was the first programme to introduce the topic to public debate

in Ireland.

Comments

Post a Comment